What the child and infant mortality statistics cover, how we produce them, and their quality and comparability. Includes definitions and latest, past and upcoming changes.

Overview

We produce annual statistics on child and infant mortality in England and Wales. These include characteristics of babies and parents, and analysis of risk factors in relation to deaths. We produce these by linking information from birth registrations, birth notifications, and death registrations in England and Wales.

It is a legal requirement to register births and deaths (and for healthcare providers to submit birth notifications) within a certain time and with correct information. This means the data is generally complete.

We and the registrars carry out thorough validation and quality assurance checks on the data to ensure our statistics are as accurate as possible.

These are accredited official statistics.

Latest changes to quality and methods

We updated this guide on 8 April 2025. Important changes to quality and methods include:

- updating the name of the child mortality (death cohort) tables to “child and infant mortality (by year of death)” for deaths in or after 2023

- updating the name of the infant mortality (birth cohort) tables to “infant mortality before their first birthday (by year of birth)” for births in or after 2022

For more information on these latest changes, as well as any past and upcoming changes, go to Changes and their effects on comparability over time.

What the statistics cover

We present statistics on child and infant mortality for England and Wales in two separate datasets:

- child and infant mortality (by year of death) - presents all stillbirths and child and infant deaths that occurred in a particular calendar year

- infant mortality before first birthday (by year of birth) - presents all stillbirths and infant deaths that occurred among children born in a particular calendar year

Why we produce both datasets

An infant death (a death that occurs within a year of birth) can occur in the same calendar year as the birth, or the subsequent calendar year.

Some users need deaths information for a group of infants born in a particular calendar year, while some need it for a group of infants that died in a particular calendar year.

The child and infant mortality (by year of death): 2023 dataset contains information on all infants that died in 2023 before their first birthday, that were born in 2022 or 2023.

The infant mortality before their first birthday (by year of birth): 2022 dataset contains information on all infants that were born in 2022, that died in either 2022 or 2023 before their first birthday.

Breakdowns in the datasets

Both datasets include breakdown by characteristics of the baby and mother, and age at death. These allow us to make useful comparisons.

Characteristics categories

- Baby’s birth weight

- Baby’s gestational age (how long a baby has spent developing inside the womb between conception and birth)

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) cause of death group

- Mother’s age at birth of child

- Mother’s country of birth

- Mother’s marital status

- Mother’s number of previous children

- Place of delivery

- Parents’ socio-economic status National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) (as defined by occupation)

These categories allow us to compare death rates – for example, between younger and older mothers, and between babies with low and normal birth weights.

How place of delivery information differs between the two datasets

We use different classifications for place of delivery between the two datasets.

For the child and infant mortality (by year of death) dataset, we get place of delivery information from birth registrations and birth notifications. We include breakdowns by the following places of delivery:

- hospitals

- other healthcare establishments

- at home

- elsewhere

For the infant mortality before their first birthday (by year of birth) dataset, we only get place of delivery information from birth notifications. We include breakdowns by the following places of delivery:

- NHS hospital – delivery facilities associated with midwife ward

- NHS hospital – delivery facilities associated with consultant ward

- NHS hospital – delivery facilities associated with consultant, GP or midwife ward inclusive of any combination

- NHS hospital – ward with no delivery facilities

- private hospital

- other hospital or institution

- domestic address

- unknown

Age at death categories

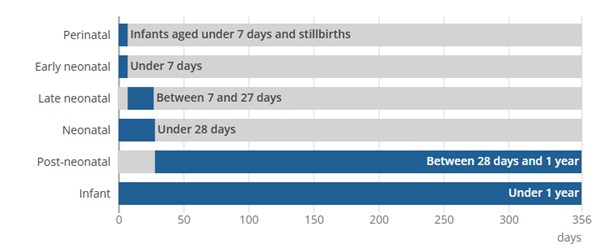

- Child (only included in the by year of death dataset): those aged between 1 and 15 years old

- Infant: those aged under 1 year old

- Post-neonatal: infants aged under 28 days and 1 year

- Neonatal: infants aged under 28 days

- Late neonatal: infants aged between 7 and 27 days

- Early neonatal: infants aged under 7 days

- Stillbirth: those born after 24 or more weeks' gestation that did not breathe or show signs of life during or after delivery

- Perinatal: those aged under 7 days and stillbirths

Figure 1

Age at death categories

England and Wales

What the statistics exclude

Both datasets exclude:

- those still-born before 24 weeks’ gestation – we categorise these as miscarriages

- births and deaths of England and Wales residents that occur and are registered outside of England and Wales

Sub-divisional breakdowns (for regions, counties, metropolitan counties, and local authorities) also exclude births and deaths of non-England and Wales residents registered in England and Wales. However, these are included for the total England and Wales figures.

Where the data come from

Birth registrations

A parent must register a birth with a registar within 42 days.

Birth registrations include information about:

- the birth and the baby – such as the date, sex, and whether one or more babies are born (known as single or multiple birth)

- the biological mother – such as her usual residence, and her age at the time of the birth

- the second parent if the parents are married or in a civil partnership, or if the second parent is present at the registration (known as joint registration)

Birth notifications

Midwifery staff present at the birth must submit a birth notification within 36 hours:

- directly onto the Personal Demographics Service (PDS) if using a PDS-compliant system

- through the National Care Records Service (NCRS) if using a non-PDS compliant system (which in turn updates the PDS)

Once the baby's birth notification is available, the PDS notifies us.

A birth notification includes information that is not included on the birth registration, such as gestation length and the baby’s ethnicity.

Death registrations

A death must be registered by “the informant” (a relative, someone present at the death, the occupier of or an official from the public building where the death occurred, or the person arranging the funeral) within five days of it occurring.

However, sometimes death registrations can be delayed if they are referred to a coroner for investigation.

Death registrations include information about:

- the death – such as cause of death, when the deceased was last seen alive, and whether a post-mortem was carried out

- the deceased – such as their sex, usual residence, place of birth, and date of birth

How we produce the statistics

Linking death registrations with birth registrations

We link death registrations with corresponding birth registrations. This allows us to get more social and biological information about the baby and parents than we could from death registrations alone.

Linking death registrations with birth notifications

Where possible, we’ve also linked death registrations with corresponding birth notifications back to 2007 – the earliest year we can apply this type of linkage. This allows us to get more information about the baby, such as gestational age and ethnicity, than we could from death registrations and birth registrations alone.

Why linking a death with gestational age and ethnicity information is important

Having a low gestational age and being from a Black or Asian ethnic group are two of the main risk factors associated with deaths in the perinatal (stillbirths and early neonatal) period. Linking these helps to provide better analysis of the relationship between gestational age and ethnic group with deaths.

Linking birth notifications with birth registrations

The registrar links birth notifications with birth registrations, which creates a unique sequence number. We use this number to carry out our own re-linkage.

If the registrar has not been able to link a birth registration and birth notification (meaning the unique sequence number is not available), we use probabilistic linkage. This means we link birth registrations with birth notifications based on the likelihood of them being for the same baby.

When we extract the data and carry out linkage for child and infant mortality (by year of death) dataset

We extract the total number of deaths occurring in a calendar year (known as the “data year” – for example, 2023) from the deaths registrations database. We do this approximately 9 to 10 months after the end of the data year to allow for late registrations.

We do not publish the small number of registrations registered after we extract the data. This is an appropriate balance between accuracy and timeliness.

We then link these deaths with birth registrations and birth notifications.

We usually cannot link around 3% of deaths (9.5% for the 2020 data year because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic – read more in Strengths and limitations). The main reasons are not being able to find a birth record, or the birth was registered outside of England and Wales.

When we extract the data and carry out linkage for the infant mortality before their first birthday (by year of birth) dataset

We extract the total number of births occurring in a calendar year (known as the “data year” – for example, 2022) from the birth registrations database and birth notifications database. We do this approximately six to seven months after the end of the data year and then link the two.

Next, we extract the infant deaths occurring in the same year as the birth, and in the following year (for example, 2022 and 2023, respectively). We extract data for both years because an infant born near the start of the data year may die during that year before their first birthday, and an infant born near the end of the data year may die in the following year before their first birthday. We do this 10 to 11 months and 22 to 23 months after the end of the data year, respectively.

This means that the infant mortality before their first birthday (by year of birth) dataset is less timely than the child and infant mortality (by year of death) dataset. However, this time lag allows us to provide additional analysis.

We then link the birth and death occurrences to decipher how many infants that were born in a certain data year died before their first birthday.

Quality of the statistics

Statistical accreditation

These accredited official statistics were independently reviewed by the Office for Statistics Regulation in February 2013. They comply with the standards of trustworthiness, quality and value in the Code of Practice for Statistics and should be labelled "accredited official statistics”.

How we quality assure the data and statistics

- The registrar carries out validation checks when a birth or death is registered.

- We carry out validation and consistency checks when we extract births and deaths data from the databases – this eliminates any errors made in the supply and recording of birth and death registrations.

- We carry out more frequent and thorough checks on registrations with extreme values for the main variables (such as age of mother and father), as these have a greater impact on the statistics.

- If we spot a registration that doesn’t look right, we raise it with the General Register Office (GRO) for additional verification – we usually only need to do this for a small number of registrations per month.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

- Producing two datasets means we provide breakdowns of child and infant mortality by year of death, and infant mortality before their first birthday by year of birth, maximising the statistics’ coverage and usage.

- The number of birth and death occurrences provided by birth registrations, birth notifications, and death registrations are generally complete and accurate; it is a legal requirement to submit these with the correct information and within a certain time period, and both we and registrars carry out validation checks (read more in How we quality assure the data).

Limitations

- There were delays to birth registrations in 2020 and 2021 because of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, which meant we had to extract births data later than usual; this affected the timeliness of the statistics, but meant we could include more late registrations and improve the accuracy.

- The pandemic also affected linkage between birth registrations, birth notifications, and death registrations for 2020 and 2021; in 2020, we could not link 9.5% of child and infant deaths, compared with around 3% for 2007 to 2009, and 2022.

European Statistical System Quality Dimensions

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has developed Guidelines for measuring statistical quality based on the five European Statistical System (ESS) Quality Dimensions. These are:

- relevance

- accuracy and reliability

- timelessness and punctuality

- comparability and coherence

- accessibility and clarity

We have integrated these considerations into the guide.

Changes and their effects on comparability over time

Over the years, we have changed how we produce child and infant mortality statistics. Sometimes this is to improve the statistics, and sometimes it is because of external changes (such as software advancements, changes to policy, or changes to legal definitions).

Changes can sometimes affect comparability of the statistics over time.

Latest changes

Dataset name changes

On 8 April 2025, we changed the name of the child mortality (death cohort) tables to “child and infant mortality (by year of death)”. This explains more clearly what we mean by “death cohort” (that the statistics are organised by year of death), and that the dataset includes statistics for infants as well as children. This name change applies to the 2023 data year onwards.

On 8 April 2025, we also changed the name of the infant mortality (birth cohort) tables to “infant mortality before their first birthday (by year of birth)”. This explains more clearly what we mean by “birth cohort” (that the statistics are organised by year of birth), and that the dataset is specifically about babies that die before their first birthday. This name change applies to the 2022 data year onwards.

The statistics themselves have not changed, so this does not affect comparability over time.

Past changes

These changes are ordered by date, with the most recent first.

Definition of a stillbirth

From the 2021 data year, we stopped classifying live births at 23 and 24 weeks as stillbirths. This had no significant effect on the stillbirth rate, so does not affect comparability over time.

On 1 October 1992, the definition of a stillbirth changed from 28 or more weeks’ gestation to 24 or more weeks’ gestation (Still-Birth (Definition) Act 1992). This means our statistics on stillbirths from the 1993 data year are not directly comparable with previous releases.

Software we use to code death registrations

We have used different softwares to code cause of death over the years. From the 2021 data year, we updated our software from to Multicausal and Unicausal Selection Engine (MUSE) 5.5 to MUSE 5.8. In line with this, we updated the hierarchical classification system we use to classify ONS cause of death groups for stillbirths and neonatal deaths for statistics.

This means ONS cause of death groups from the 2021 data year onwards are not directly comparable with 2014 to 2020.

Read more about the impact of implementing Iris.

From the 2018 data year, we updated our software from Iris to MUSE 5.5. MUSE 5.5 increased the automation of coding and operated based on internationally agreed decision tables to reflect the ICD-10.

This change slightly reduced comparability with previous releases, but increased accuracy in coding causes of death.

Read more about the impact of implementing MUSE 5.5.

On 1 January 2014, we updated our software from Medical Mortality Data Software (MMDS) to Iris. Iris incorporated official updates to the ICD-10 approved by the WHO, helping to improve international comparability.

For stillbirths and neonatal deaths, Iris coded maternal condition mentioned on the death certificate to chapter XVI (certain conditions originating in the perinatal period) rather than chapter XV (pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium).

These changes limited the comparability of the “antepartum infections” and “infections” cause of death groups from the 2013 data year with previous releases.

Ethnic groupings

In 2021, we updated baby ethnic groups to better align with the groups used in Census 2021 back to the 2019 data year, meaning they are not directly comparable with previous releases.

In 2020, we introduced three new tables in the child and infant death (by year of death) dataset on the number and rates of live births, stillbirths, and infant mortality by ethnicity. These were previously available in our Births and deaths by ethnicity dataset for 2007 to 2019 .

This does not affect comparability of the statistics over time.

How we present unlinked death

We have made several changes to how we present unlinked deaths (deaths that could not be linked to a birth) over the years.

For the 2020 data year, we created a separate category for unlinked deaths.

For the 2019 data year, we included unlinked deaths in all tables in the by year of death dataset. We included them in a “not stated” category in tables that analysed birth registration variables, and presented them separately in tables that analysed death rates for linked deaths.

Before this, we had left unlinked deaths out of some of the tables completely.

Geographic boundaries

Since the 2017 data year, we’ve used the latest geographic boundaries for sub-divisional breakdowns.

Any changes to geographic boundaries can affect the comparability of sub-divisional breakdowns over time. Find specific changes in our Data sources guide to mortality statistics.

When we extract data for the infant mortality before their first birthday (by year of birth) dataset

From the 2015 data year, we began extracting death registrations 10 to 11 months and 22 to 23 months after the end of the data year, respectively.

The change meant we captured 5% to 6% more late registrations, and that statistics from the 2015 data year are not comparable with previous releases.

Read more about our current approach in When we extract the data and carry out linkage for the child and infant mortality (by year of death) dataset.

What datasets we publish

From the 2015 data year, we combined our Birth cohort tables for infant deaths dataset and Pregnancy and ethnic factors influencing births and infant mortality dataset into one dataset: infant deaths before their first birthday (by year of birth) (previously known as infant mortality (birth cohort) tables in England and Wales). We made this change based on feedback from the infant mortality user consultation.

Information collected about previous children on birth registrations

From May 2012, birth registrations started including the number of previous live births and stillbirths all mothers had had, rather than just those married mothers had had with the current or former husband. This change came about because of amendments to the Population (Statistics) Act 1938.

This simplified the question and led to improved accuracy in responses, but means statistics from the 2014 data year onwards are not directly comparable with previous releases.

Read more about the impact of this change on our birth statistics:

- How changes to the Population Statistics Act will affect birth statistics (PDF, 66.2KB)

- Quality assurance of new data on birth registrations, as a result of changes to the Population Statistics Act – from May 2012 onwards (PDF, 539KB)

- Childbearing by registration status in England and Wales, using birth registration data for 2012 and 2013

How we code country of birth

In 2012, we started categorising the statistics by the most advantaged parent’s socio-economic classification (a “household-level classification”). Previously, we had automatically categorised the statistics based on the father. This was because many mothers did not have a paid occupation or chose not to state their occupational details on the birth registration.

In 2011, we rebased the NS-SEC on the new Standard Occupational Classification (SOC 2010) to categorise socio-economic class. This change meant classifications were based on employment conditions instead of skills to more accurately describe modern occupations.

Both of these changes means statistics from the 2012 data year onwards are not directly comparable with previous releases.

Recording births registered to same-sex couples

From 1 September 2009, two females in a same-sex couple became able to register a birth under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008.

From the 2010 data year, we categorise births registered to same-sex couples:

- in civil partnerships as "marital births"

- outside of civil partnerships as "non-marital births"

The numbers of births registered to same sex-couples is relatively small, so this change has a negligible effect on comparability over time.

We include footnotes in the datasets stating the number of births registered to same-sex couples included in the numbers.

Statistical classifications of disease systems we use to we code cause of death

We have used different revisions of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD) to code cause of death over the years.

From the 2009 data year, we switched from using ICD-10 v2001.2 to ICD-10 v2010.

From the 2000 data year, we switched to using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) to code causes of death, based on the recommendation of the WHO. This replaced the ICD-9, which we had used since 1979.

These changes limited comparability with previous releases, but resulted in:

- diseases and groups of conditions that reflected more up-to-date medical knowledge

- improved selection of the underlying cause of death

- improved international comparability

Death registration certificates

In 1986, England and Wales introduced new certificates for registering neonatal deaths (infants that died aged under 28 days) and stillbirths in line with a recommendation from the World Health Organization’s (WHO).

These are different to standard death certificates – they do not assign a single underlying cause of death, and instead give certifiers more flexibility to report on multiple relevant diseases in both the infant and the mother.

This meant we could no longer directly compare a single underlying cause of death for neonatal deaths and stillbirths with postneonatal deaths (infants that died aged between 28 days and 1 year).

To address this, we developed a Classification system of broad Office for National Statistics (ONS) cause of death groups (PDF, 72KB), where a computer algorithm directs any mention of a “mechanism” that led to death on both death certificate types to the first appropriate cause group.

This allows us to directly compare stillbirths and neonatal deaths with postneonatal deaths, despite the differences in registration.

Upcoming changes

We currently have no plans to change the methods in the near future.

Comparability and coherence with other statistics producers

Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK

Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK's (MBRRACE-UK) Infant mortality statistics are not comparable with ours because of the following differences.

| ONS | MBRRACE-UK |

|---|---|

| Includes deaths of children up to 15 years | Includes infant deaths only |

| Includes all live-born babies, including those born before 24 weeks | Excludes live-born babies born before 24 weeks |

| Includes stillbirths from 24 weeks' gestation in line with the legal definition | Includes stillbirths from 22 weeks' gestation |

Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency

Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency's (NISRA) Child and infant mortality statistics are not comparable with ours because of following differences.

| ONS | NISRA |

|---|---|

| Based on date of death occurrence – gives a more accurate representation of deaths in a given year and helps track trends over time | Based on date of death registration – reduces the delay in producing statistics, but result in less complete statistics because late registrations are not captured |

National Records Scotland

National Records Scotland's (NRS) Child and infant mortality statistics (part of their vital events statistics) are not comparable with ours because of the following differences.

| ONS | NRS |

|---|---|

| Based on date of death occurrence – gives a more accurate representation of deaths in a given year and helps track trends over time | Based on date of death registration – delays are shorter in Scotland, so little difference between death occurrence and registration dates |

Users and uses of these statistics

A range of organisations and government departments use our child and infant deaths statistics to inform services and policies, and ensure targets are met. For example:

- the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) includes our statistics in their child and maternal health profiles; local organisations use these to create reports, tools, and other resources to plan services based on what their area needs

- our statistics are used to monitor the NHS’s, the Welsh Government’s and the UK Government’s progress towards targets outlined in the NHS outcomes framework, such as reducing deaths in babies and young children

- the United Nations (UN) Statistics Division uses our statistics alongside statistics from Scotland and Northern Ireland to monitor the UK’s progress towards global indicators, as part of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals

Other users include academics, researchers, charities, and the media.

Definitions

For definitions of how we categories different ages at death, go to Age at death categories.

Linkage

The matching of death registration records to their corresponding birth registration record and/or birth notification record, and birth registration records to their corresponding birth notification record.

Occurrences

The number of:

- deaths according to the date on which the death occurred

- births according to the date on which the birth occurred

Registrations

The number of deaths according to the date on which the deaths were registered, and the number of births according to the date on which the births were registered.

Underlying cause of death

“The disease or injury which initiated the train of morbid events leading directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury”, in accordance with the rules of the International Classification of Diseases (excludes deaths that occurred under age 28 days).

Related links

-

Child and infant mortality (by year of death)

- Released:

- Dataset

Live births, stillbirths and linked infant deaths occurring annually in England and Wales, and associated risk factors.

-

Infant mortality before their birth birthday (by year of birth)

- Released:

- Dataset

Annual statistics on births and infant deaths based on babies born in a calendar year that died before their first birthday linked to their corresponding birth notification and their corresponding death registration.

Child and infant mortality in England and Wales: 2023

- Released:

- Statistical article

Stillbirths, infant and childhood deaths occurring annually in England and Wales, and associated risk factors.

Data source guide to mortality statistics

- Released:

- Data source guide

Supporting information for mortality statistics, which present figures on deaths registered in England and Wales in a specific week, month, quarter or year.

Data source guide to birth statistics

- Released:

- Data source guide

Supporting information for birth statistics, which present figures on births that occur and are then registered in England and Wales. Figures are based on information collected at birth registration.

Cite this page

Office for National Statistics (ONS), updated 8 April 2025, ONS website, quality and methods guide, Child and infant mortality In England and Wales quality and methods guide

Contact details

Population Health Monitoring Group

health.data@ons.gov.uk

Telephone: +44 1329 444 110

Monday to Friday, 9am to 4pm